I was playing around with this piece thinking that it might be a good way to bring people into the UBI debate (believe it or not) when, inevitably, the issue of refugees hit the headlines when Winston Peters shot down Labour’s plan to increase NZ’s refugee numbers.

One of the good (or bad) things about this was that the comment section in STUFF gave me an insight into the general public attitude to this issue. It was not encouraging. I confess, I chickened out and decided not to submit it. The comment section was so vitriolic that putting my head above that parapet was something I was unwilling to do unless the answer was overwhelmingly obvious.

As it is, even if the economic debate over migrants and refugees is not completely conclusive, I think that it is so difficult to conclude that they are a cost that we might as well ignore this as an issue.

However, I actually don’t think the economics are the actual issue for most people.

__________________________________

There are many arguments for and against accepting immigrants and refugees into a country. The big debates revolve around humanitarian, cultural, security, infrastructure, and, inevitably, economic concerns.

Of these, you would think that determining if a group are net economic contributors to the country, or not, should be a relatively easy problem to solve.

If the answer is reasonably clear we can get it out of the way early on.

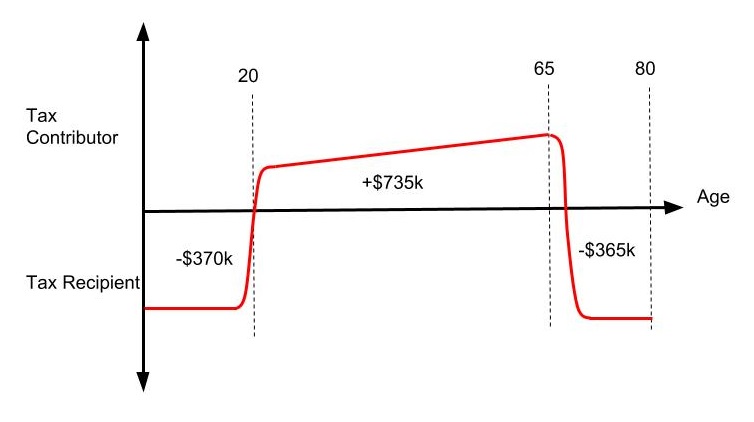

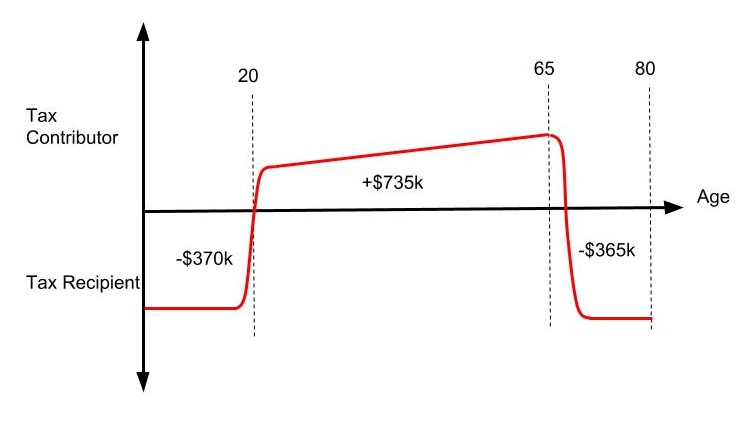

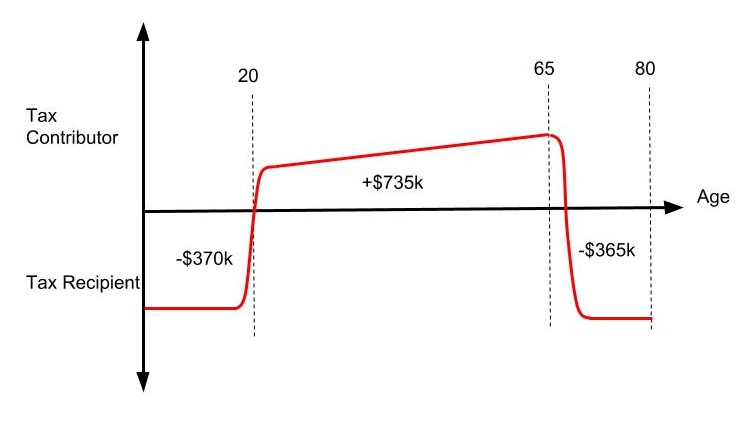

As it happens a “back of the envelope” analysis indicates that as a group, immigrants and refugees are odds-on favourites to be net contributors to society. To understand why, consider the figure below which roughly plots the net tax contributions throughout the life of an “average taxpayer”, along with some rough numbers.

Figure: Tax contributions and expenses for the “average taxpayer”

First, the “average taxpayer” is a compilation of everyone in society, combining high and low earners, and the tax that they pay and spend over the course of an average lifespan.

There are some costs that cannot be tagged to a particular period of life and which are incurred by all residents. Think of these as “core government services” such as roads, defense, law and order and such like. These are a consistent cost paid every year by everyone.

Other contributions and expenses occur during defined periods of life.

Until they reach around 20 years of age the average taxpayer will be costing society money. In this period of their life, they are unlikely to be paying tax while going through the expensive process of being born, surviving past 5, getting a compulsory education, and transitioning to work. This is all very expensive.

Between the ages of 20 and 65, the average taxpayer will be working, contributing tax dollars while not incurring any predictable expenses specific to that age bracket. This is when they make their positive contribution to the tax take.

At 65 they will get NZ superannuation, work less, and become increasingly dependent on the health system. They are almost certainly going to use more tax dollars than they contribute.

The key takeaway from this analysis is that if you are an average taxpayer then, give or take a bit, all these costs and benefits should nett out to zero. Your contributions in the middle years of life should basically equal what it costs in your early and later years. And that is the way it should be.

It’s a bit rough, and there are also a few wrinkles not accounted for, in particular, whether the average taxpayer has any tertiary training or not and how to treat consumption taxes during retirement, however, it’s good enough to make some predictions.

For example, this model represents the average person born here. What about if you move here later in life?

Consider the “economically optimal” immigrant or refugee – someone who arrives ready to work at 20. In this case we get all the tax contributions in their working life, still have to pay the costs post 65, but miss out having to bring them into the world and educate them. By removing this large expense at the beginning of their life, to be tax neutral they really only have to contribute around 70% of the average tax as someone born in NZ. In short, they are unlikely to be a drain on the public purse.

What if they are younger? While there are clearly more education costs, the chances of them being more like the “average taxpayer” become higher and higher the younger they get. It would be extremely unlikely that an immigrant who arrived at age 1 would end up vastly different to a born and bred kiwi, and we don’t complain about them.

Clearly, things do get more problematic as immigrants get older as they have fewer years to contribute towards their retirement. This is particularly an issue when considering “family reunification” policies, and is justifiably treated with care. However, assuming they can earn roughly the same as average taxpayers, migrants who end up eligible for superannuation would have to be older than 45ish before this became problematic.

Refugees have a bit more of an economic headwind to overcome as it is deemed necessary to spend around $80-100K to ease their passage into society. However, given it costs around $370K to get a NZ born resident to age 20, they are probably still odds-on to be a positive contributor if their average age is between around 35-40.

Remember, that this analysis is comparing the average immigrant and refugee with the average taxpayer. Everyone will have specific examples which differ in either positive or negative ways. Economically it is fairer to consider immigrants and refugees as a group allowing their foibles and benefits to offset each other while leaving the group’s true overall contributions intact, just like we do for all New Zealanders.

It is also worth considering that there is an even more “economically optimal” migrant than described above. These arrive aged around 20, work for a while, start pining for home and leave before obtaining any rights to a pension. It is pretty much all upside for us. If this sounds familiar it is because NZ is pretty good at producing these for the benefit of other countries. We call it “having an OE”.

If someone spends 10 years overseas during their working years then they have to pay around 20% more than the average amount of tax while in New Zealand to break even over their lifespan.

In no way am I wanting to discourage people from taking an OE as I think it adds to the cultural fabric of New Zealand. However, if you feel the need to point the economic gun at anyone for not contributing their fair share, then they are a more likely target.

Depending on your view of the world there may be significant concerns involved with immigration, however, financial costs are unlikely to be a legitimate one. If money was the only issue we should be looking for as many as we can get. However, invariably, economics will not be the only issue.