While searching for a topic that I could feasibly imagine writing about on a semi-regular basis, it crossed my mind that yes, I do enjoy a good graph! I particularly enjoy graphs that illustrate a reasonable course of action i.e. they are useful.

Of course, I also enjoy pillorying graphs that are complete rubbish. Especially when they are being used to promote a perspective with a lot more certainty than the data would support.

Therefore, I thought I would try publishing a graph every month that I think is worthy of discussion – for good or bad reasons. Surely I could manage one a month!

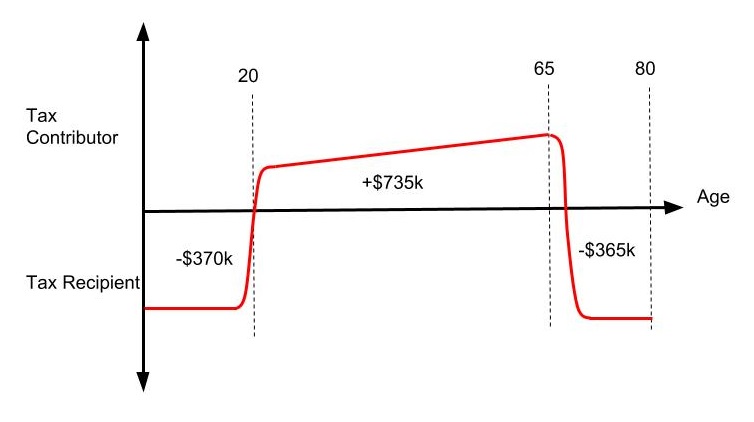

To kick things off, the graph below was published in The Economist in an article considering the most effective way to reduce carbon, and therefore address climate change (Giving up the carbs: What is the cheapest way to cut carbon? The Economist, Feb 27, 2021). This article was in response to Bill Gate’s book addressing this issue. While well-received for providing a realistic, science/engineering based perspective on what was ACTUALLY required, unfortunately, its impact was slightly dented by revelations of his involvement with Jeffrey Epstein and then his subsequent divorce. Shame.

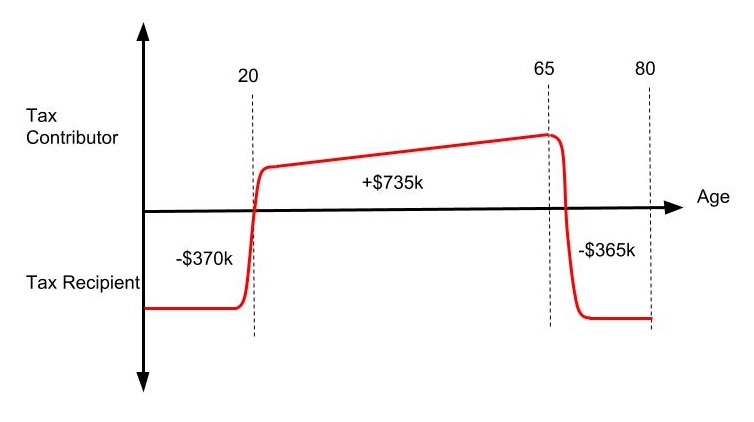

What does the graph show?

- The x-axis shows the total amount of carbon that can be abated (gigatonnes of CO2)

- The y -axis shows the cost ($’000/ per ton of CO2) that it will cost to get rid of that carbon

- The data then shows the cost of reducing carbon from key areas, with the lowest (in fact negative) costs shown first.

What does the tell us?

If you were serious about addressing carbon emissions then:

- Typically, there is a whole lot of low hanging fruit where we can get significant reductions for a relatively low cost.

- Alas, this low hanging fruit is not particularly “sexy”, and is sometimes feels inadequate – i.e. big wins can be achieved by burning carbon-producing gas rather than really, really carbon-intensive coal. Still bad, but a lot better than the alternative.

- Electric cars/trucks will be necessary but do not return a great bang for your buck.

- There is a lot of carbon emissions where we simply do not have the technology to deal with at the moment no matter how much we pay.

Why do I like this graph?

- Admittedly I like sticking it to people who talk big, but don’t do the basics well. There is a whole lot of stuff that will make a real difference but is unlikly to make the papers.

- I like that it leads you to counterintuitive results. Instead of spending money of buying an electric car, if you area really seriouse about reducing carbon there are more effective things you can do, even if they are done by others.

- Which makes NZ’s purchase of carbon credits from other countries seems more sensible. We could spend money reducing carbon here but the options are probably quite expensive. We can get more carbon reduction bang for our buck by paying other people to do it. Afterall, the world doesn’t care where the carbon reductions come from!

- Once again, this graph rams home that some mechanism for pricing carbon is probably the best chance we have of reducing carbon in a sensible way as it allows us to rank the most cost effective methods.

- However, it is also clear that we are gong to need a lot more research! We simply have to get inventing different ways to solve the big chunck of carbon which we have no feasible way of dealling with at the moment. I personally think that lifestyle changes are not going to cut it, we have to engineer our way out of this!

How could the graph be improved?

- The biggest improvement would be to change the x-axis scale to a percentage of the total carbon currently emitted. While the current figures look large it is unclear if the carbon that can feasibly be reduced is a significant percentage of what is emitted, or if the amount that we have no solution for is actually overwhelmingly large, as the axis has no upper limit. In its current form, it looks like it is about 15% of emissions that we can’t deal with at the moment, I suspect it is much higher.

Any thoughts on this graph and/or my interpretation would be well received. If you have any personal favourites feel free to send them in.